This article was first published in the Summer 2023 issue of On Watch.

By Chris Lombardi

If only the military were nearly as “woke’ as Congress thinks it is.“

It’s ironic,” Maj. Alan Kennedy told me on June 1, 2023. “All we got out of it is a handful of renamed military bases.” By “we” Kennedy meant those opposing racist extremism in the military, including the Black Lives Matter protests that first brought Kennedy to MLTF.

And by “it” Kennedy meant the changes promised by the Pentagon after the national response to the murder of George Floyd.

As this article was going to press, the House Armed Services Committee completed its first draft of the 2024 NDAA – featuring amendments designed to undermine the Pentagon’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives. As the Military Times’ Rebecca Kheel, notes, while Congress seeks to remove what HASC calls Biden’s ‘radical race ideology,’ there’s little DEI in evidence: frankly, Kheel adds, “there have been no substantial changes to diversity training in the military since the start of the administration.”

Much of the Pentagon’s most visible DEI efforts date to 2020, the year then–Captain Alan Kennedy was tear–gassed in Denver as he participated in the national response to the police killing of George Floyd and was disciplined for writing an op–ed about it. “2020 initiated a rash of talk about diversity in the military,” Kennedy told me in a recent interview.

The military has had a long and rocky history of dealing with racism and extremism (as I described last year for On Watch). That history has often included similar initiatives, including the substantial Military Equal Opportunity program that Kathleen Gilberd describes in this issue. As Task and Purpose noted last year, “The Pentagon didn’t order service members to reject supremacist organizations until 1986, nearly a decade after more than a dozen Marines belonging to the Ku Klux Klan had freely handed out leaflets on base for a white supremacist group with a long, violent history of terrorizing minorities.”

Forty years later, the Center for Strategic and International Studies found a recent increase in the percentage of domestic terrorist plots and attacks perpetrated by active-duty and reserve personnel with 37 percent of lone-wolf attacks perpetrated by either such figures or recent veterans. In 2021 CSIS’ Seth Jones cited Army Private Ethan Melzer, arrested in June 2020 after leaking sensitive information to the Order of the Nine Angles (O9A), an explicitly Satanic neo-Nazi and white supremacist organization, hoping to induce the Order to massacre Melzer’s own unit. Jones also mentioned the Capitol insurrection of January 6, 2021, many of whose perpetrators carried Confederate battle flags into the Senate Office Building and over 15 percent of whom had military affiliations.

While the raw numbers of military-affiliated perpetrators may be small, the effects can magnify given the military’s special tools. MA National Guard airman Jack Teixeira, currently being court-martialed for leaking intelligence files to his Discord server, was reportedly hoping to impress a much-larger Discord community called Thug Shaker Central, which featured Nazi imagery in its celebration of gun culture.

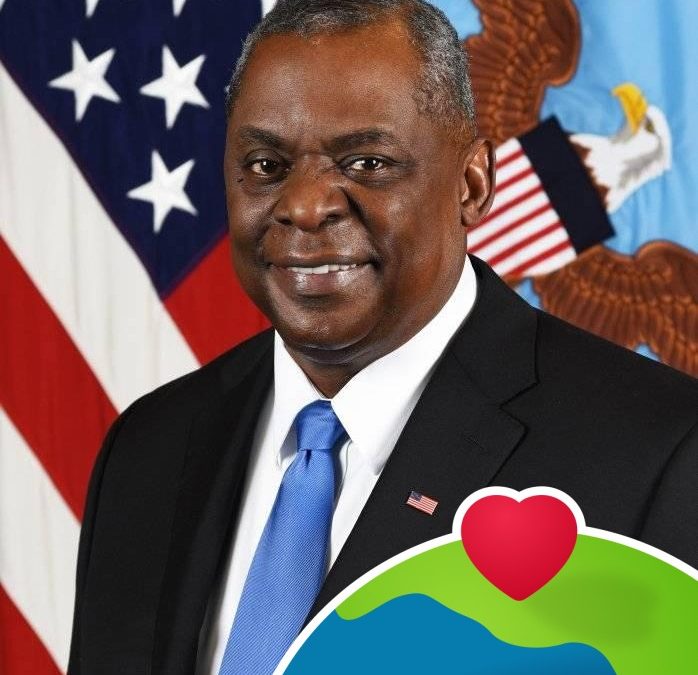

The Countering Extremist Activity Working Group, convened by SecDef Austin in early 2021, made some specific recommendations on training:

- Create an annual, stand-alone, computer-based Joint Force “extremist activity”

- Require “in-person discussions about extremist activity in periodic training addressing unit climate and culture”

- Counter-extremist activity training “tailored for Senior Enlisted Leaders (SELs), law enforcement, recruiters, and legal advisors.”

Many of these recommendations were included in the 2022 NDAA, only to be removed from the 2023 version. Which, if any, were actually implemented? What is DEI trying to accomplish, and are any of its initiatives making a difference for servicemembers facing racism in the ranks? What are the actual levels of the latter?

Trying to get answers to any of that is tricky. The Freedom of Information Act seems of little help: a recent MLTF request for recent data on discrimination yielded on unwieldy spreadsheet redacted for members’ privacy, which came with this proviso: “As of FY 2020, this section is no longer required to be completed by the Services.” Meanwhile, when the nonprofit American Oversight submitted a FOIA asking for data about white–supremacist troops, the resultant flood included investigations going back as far as 1998, when Timothy McVeigh was still alive, and a probe of Klan activity on the U.S.S. Theodore Roosevelt in 2008, which provides context and verification for Jonathan Hutto’s account in this issue of On Watch.

One could write another article exploring the data revealed by American Oversight – about the 2005 “Hammerskin” white power rally in Florida, about white sailors protesting that a Black man had been elected their Commander-in-Chief, or about the National Guardsmen in Binghamton/Ithaca, historically Klan country, discharged between 2021-22, one telling investigators that he was a member of the III% movement. But none of that data comes close to our task here: has ODEI actually implemented its anti-extremism training?

According to Pentagon spokesperson Sabrina Singh, training is the one thing the DoD has actually completed, “implemented across the Department.” Asked in a May press conference: “Where do the department’s efforts related to extremism stand?”, Singh added that the Pentagon was still getting started on the other recommendations from the working group, which “include military justice and policy, support an oversight of insider threat program, investigative processes and screenings capability, and education and training.” None of which will even get started if the Congressional revolt above comes through. But is there really an active, dynamic anti-extremism program anywhere in the Department of Defense? What exactly has been implemented?

According to Major Alan Kennedy — who gained his current rank in 2022, after the Army overturned its own reprimand for his 2020 editorial – DoD hasn’t gotten much past that first recommendation, or the “stand-alone, computer-based” training module. That model was much in evidence at the now-famous “stand down” mandated after January 6.

These stand-down slides, now available online from DoD, the Army, and the Marines, start by emphasizing the meaning of the oath troops take, going on to declare that “actively espousing ideologies that encourage discrimination, hate, and harassment against others” violates the oath and “will not be tolerated.” Impermissible behaviors include liking and sharing extremist materials posted in social media, and the slides include case studies of such behavior. All of which feels promising, but less so if you envision those phrases droned by a Colonel to a roomful of servicemembers. The PowerPoint refers to “small group discussions,” but pandemic protocols rendered most of the trainings fully remote, with troops logging into Zoom and commanders going through the talking points in turn — all ending with the need to report extremist behavior to the commander.

Troops surveyed by Military Times were similarly unimpressed. One lieutenant from Naval Air Station Jacksonville, called its script forced, adding that the leadership was “reluctant to have in-depth discussions, brushing off questions, or just moving the conversation to the next topic. It was very surface-level, without significant substance.”

Kennedy adds that the same goes for Equal Opportunity training, mostly limited to here’s your EO coordinator. If you’ve been discriminated against, talk to this person, call this number. “They don’t talk about racism. They don’t talk about systemic racism, structural racism. So I think there may be more of a perception that the military does this than a reality.”

What about the small-group discussions on extremism recommended by the Pentagon? MLTF member Ana Maria Bondoc, who recently surveyed the terrain at Fort Bragg (now Liberty), said that depends on soldiers’ installation and unit. “There were some group discussions attempted in response to George Floyd’s killing, which did not continue after a few months. More formal trainings occur as part of inprocessing, specialized schools, or leadership training.” Bondoc notes that some of the latter have included discussions of “implicit bias” also known as “unconscious bias.” Bondoc also pointed to extensive PowerPoint sessions from the MEO Program, as well as the more interactive 30-minute scenario videos shown on Eric Washington’s YouTube channel. Bondoc is a member of MLTF’s AntiRacism Committee, which will continue to seek further details on the military’s training efforts.

Meanwhile, the realities of military racism remain. In June 2023, a Pentagon review surfaced about inequities in military justice, showing prejudicial behavior by commanders and supervisory personnel contributed to the fact that Black personnel are 2.2 times more likely to face court-martial and conviction. The August 2022 report, from the Internal Review Team on Racial Disparities in the Investigative and Military Justice Systems, touted its 18 recommendations, most of them focused on – wait for it! – better training.

For now, at least, there’s a handful of renamed bases. Those bases still named for Confederate figures, 158 years after the Civil War ended, were highlighted by members of Congress in 2020, trying to sort out how to respond what felt to many, including then–Captain Kennedy a transformative moment. As a result, Fort Polk is now Fort Johnson, replacing the name of a Confederate general who fought against the United States throughout the Civil War with that of William Henry Johnson, decorated for World War I service with the Harlem Hellfighters, while Fort Bragg is now Fort Liberty and Fort Hood renamed Fort Cavazos. Those changes, said AM Bondoc, seem at the new Fort Liberty to be mostly on the surface: “Although there’s a lot of press coverage about it, most signage hasn’t changed in Fayetteville, NC. In everyday conversations/emails etc., the old names are still commonplace.” Meanwhile, some of the Republican politicians who oppose DEI are also pledging to reverse those base re-namings, returning them to the names of White men who fought a traitorous war because they didn’t see Black people as humans.

The need to replace those base names could have been grist for those “small-group discussions” promised by the Pentagon years ago. But that would require commands to be serious about fighting racism in the military, at least as serious as the 1971 Defense Race Relations Institute, called by historians “the most progressive and forward-looking race relations experiment in existence.” Instead, it seems, we have the slapdash PowerPoint trainings described above, which may disappear thanks to the 2024 NDAA.

Full disclosure: the author of this article is also on MLTF’s anti-racism subcommittee, and we will continue to search for details on what training looks like on the ground. Our upcoming CLE on September 13, 2023, will feature both Alan Kennedy and Jonathan Hutto, who can be our Virgils as we descend to the military’s underworld. Meanwhile, we continue to serve clients in real time, with resources and support in their own fights against military racism. If you’re interested in the anti-racism subcommittee, please contact the author at chrisaintmarchin@protonmail.com.

Chris Lombardi is a former staff member with the Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors, and has been writing about war and peace for more than 20 years. Her work has appeared in The Nation, Guernica, the Philadelphia Inquirer, ABA Journal, and at WHYY.org. The author of I Ain’t Marching Anymore: Dissenters, Deserters, and Objectors to America’s Wars (The New Press), she lives in Philadelphia. She is currently on the steering committee of the Military Law Task Force.