Book Review

By Matthew Rinaldi

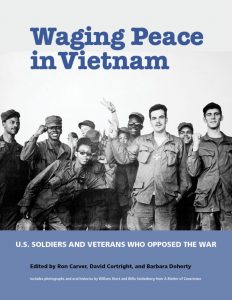

Ron Carver, David Cortright, and Barbara Doherty, editors

New Village Press, 2019

320 pages • 8.5 x 11 inches

200 black & white photographs

Waging Peace is a recent addition to the struggle over how our culture remembers the experience of U.S. veterans of the war in Vietnam.

Among those of us who were involved in the G.I. anti-war movement during those years, there is consensus that, as the war dragged on, there was widespread disaffection within the ranks of the U.S. military. The oft-quoted words of Col Robert Heinl in the 1971 Armed Forces Journal describes the reality we saw:

“By every conceivable indicator, our army that now remains in Vietnam is in a state approaching collapse, with individual units avoiding or having refused combat, murdering their officers and non-commissioned officers, drug ridden, and dispirited where not near mutinous.

Elsewhere than Vietnam, the situation is nearly as serious. Sedition, coupled with disaffection within the ranks, and externally fomented with an audacity and intensity previously inconceivable, infests the Armed Services.”

Many tens of thousands of G.I.s were radicalized. Over 25,000 joined Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW), which continued long after the war had ended. VVAW fought to have PTSD recognized as a service-related injury and to prevent further wars of U.S. aggression.

Most veterans of the later years of the war leaned left and were sought after by peace groups and radical organizations. Hal Muskat, a Vietnam veteran who was an organizer at Fort Knox, remembers participating in the veterans’ contingent of an anti-war march and being swamped by people trying to hand him leaflets.

Yet there is a counter-narrative being pushed by the right wing in the U.S. Apparently sparked by the three Rambo movies made during the Reagan presidency, Sylvester Stallone as Rambo angrily rants about being spat upon when he returns from Vietnam. The narrative which has been built is that civilians, particularly those in the peace movement, were disrespectful of returning vets, mistreated them, insulted them and made their lives difficult.

This has built into a crescendo since 9/11. Now we live in an era of hyper-patriotism, where U.S. flags are everywhere and service members are all transformed into heroes and heroines, whenever and however they performed their service. The notion seems to be that any disrespect for the flag or our country’s overseas wars is an echo of the “disrespectful” peaceniks from the sixties and seventies.

Efforts to portray the real disaffection of Vietnam era troops began with the publication of The New Soldier in 1971 by John Kerry and VVAW. It contained moving and at times heartbreaking photos of Vietnam vets fresh from the war, many of them already discharged, wearing beards, long hair and ragged clothing. This was followed by my long, very detailed and frankly boring piece “Olive Drab Rebels,” printed by 1974 by Radical America and reprinted in 2002 by Antagonism Press (available online at https://libcom.org/library/olive-drab-rebels-military-organising-vietnam-rinaldi). This was followed by David Cortright’s classic book on the topic, Soldiers in Revolt, in 1975.

The most useful work is the film Sir! No Sir! produced by David Zeiger. It offers an intimate look at the organizers and activists in the military, shatters Rambo’s spitting fiction and is extremely useful as a teaching tool. There followed Dangerous Grounds by David Parsons in 2017, perhaps the most detailed and accurate account of organizing efforts involving active duty soldiers, veterans and civilian coffeehouses at Fort Lewis, Fort Hood and Fort Jackson. (See our review of Dangerous Grounds in On Watch in 2017 for a full history of the G.I. movement.)

Where does Waging Peace fit in? The book is coffee-table size and priced accordingly – $65 in hardcover and $35 in paper. With 239 pages of text and graphics, the potential is enormous. Growing out of an exhibit the authors put together in Vietnam, the book could have been deeply moving. Instead, it feels thrown together and jumbled. It has no center or consistent theme.

Some of the omissions are troubling. There were some serious problems at the coffee house at Fort Jackson, where one activist, Lenny Cohen, was sentenced to three years in jail for disturbing the peace. Not mentioned. Wade Carson, a Vietnam combat vet, led a rebellion at the Fort Lewis stockade. Not mentioned. Yet an article on the problems military deserters faced in getting to Canada is introduced by a civilian who thinks he would have deserted, until he takes us step by step through his pre-induction physical, which he failed. Poor choices when you have 239 pages available.

Some omissions are clearly political. Left wing parties sent a few hundred comrades into the military as organizers, yet no mention is made of that fact. Dennis Mora of the Fort Hood Three was in the Communist Party, Howard Petrick and Andrew Pulley at Fort Jackson were in the Socialist Workers Party, and Andy Stapp joined the Workers World Party. Progressive Labor had members throughout bases stateside. They are erased, the same way the recent PBS/Ken Burns series on the war erased G.I. resistance entirely.

There are also some great essays in Waging Peace. Major Hugh Thompson intervened to save lives at the My Lai massacre. The L.A. Times calls him “the forgotten hero.” Though he passed away in 2006, Waging Peace carries his story through an essay written after he was interviewed. Flying above the massacre in a helicopter, Major Thompson states:

We were seeing bodies everywhere. At first, we didn’t know what was going on. And we surely couldn’t believe our own people would do this. Then it finally sank in – U.S. soldiers were killing unarmed civilians.

Major Thompson landed the helicopter and with the help of Larry Colburn, his gunner, and Glenn Andreotta, his crew chief, they literally threated to turn their guns on U.S. soldiers if the killing did not stop. The massacre ended immediately. Waging Peace correctly calls all three men heroes.

Lt. Susan Schnall is recognized for flying a Navy plane over San Francisco and dropping anti-war leaflets. Dr. Howard Levy is recognized for refusing to train Green Berets. Essays by Paul Cox, Dave Kline and Carl Dix are very moving. And Kelly Dougherty brings us to the present by writing about the sexual harassment she regularly faced in today’s modern military, which she calls out for its misogynistic culture. She also highlights some of the regular abuses of civilians she witnessed during her deployment. Her unit protected trucks used by military contractors when the trucks broke down, and destroyed the trucks’ contents when they could not be salvaged:

Sitting in a Humvee turret pointing an automatic machine gun at bewildered kids while we burned food didn’t quite match the image of heroism that military mythology seeks to evoke.

She became one of the founders of Iraq Veterans Against the War, writing, “I believe that veterans have incredible power to create change by using our experience and perspective to challenge the narratives that perpetuate the violence and injustice of war and militarism.” These essays are an important addition to the history of the U.S. military.

Sadly, the graphics in the book are often badly handled. Many of the photographs of veterans are tiny, some 2½ inches by 3½inches, so small that you get no feeling for the person depicted. Many leaflets are printed at one-quarter of their original size and thus are literally unreadable – a serious graphic mistake.

Yet Waging Peace is an addition to the work designed to ensure that G.I. resistance to the Vietnam War is not erased from our cultural memory. This book is good. It could have been great.

Matthew Rinaldi worked at the anti-war coffeehouse at Fort Lewis from 1969 to 1971 and was on the staff of the USSF from 1971 to 1973. He became an attorney in 1983 and is currently on the MLTF steering committee.