By David Gespass

Kelly-Ingram Park in Birmingham, across the street from the 16th Street Baptist Church and the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, contains a series of sculptures commemorating Birmingham’s history in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950’s and 60’s. The last built, and most controversial, is one dedicated to the “foot soldiers” of the struggle, black school children who braved fire hoses, dogs and freezing jails to demand something approaching equality. It shows a boy confronted by a cop with a dog, teeth bared and on hind legs, at his side. It was controversial because, to many (white) members of the community, it evoked the harshest cruelty of a time they said we had moved beyond. But, over the years, it has become iconic and is arguably the most important of the sculptures in the park. Those young, courageous foot soldiers were the true heroes of the Birmingham Movement. Not Martin Luther King, not even Fred Shuttlesworth, whose courage matched that of the youth, would have mattered but for the foot soldiers.

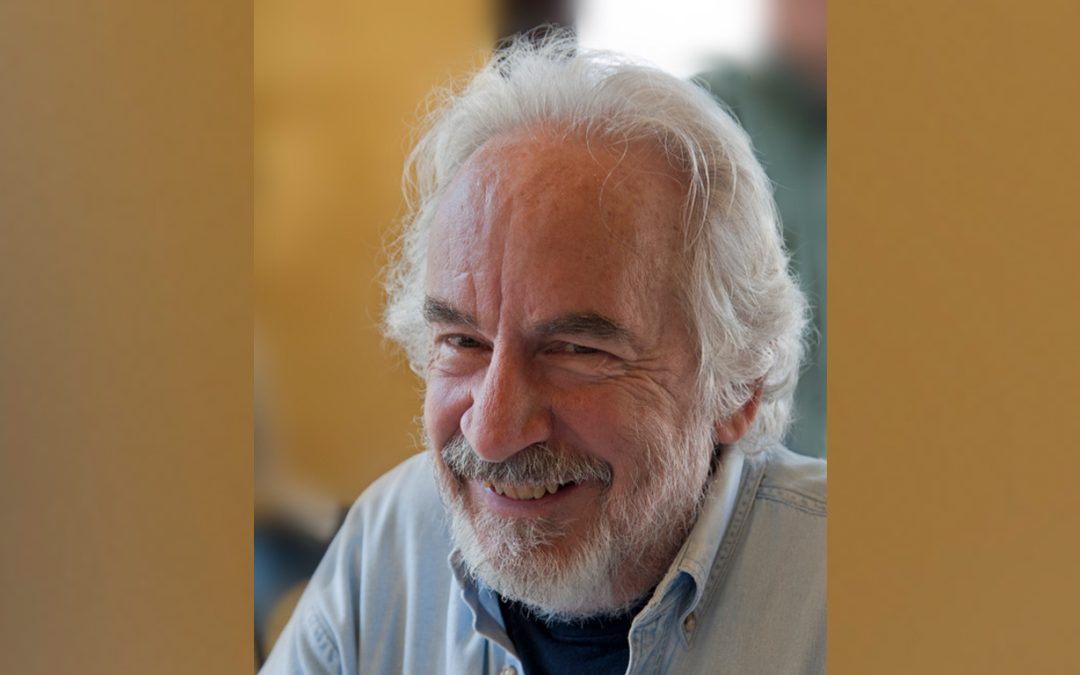

Reber Boult, our late comrade and long-time MLTF steering committee member who passed away on December 30, 2020, was a legal foot soldier. He was not a legend like Arthur Kinoy. He did not bask in the spotlight like Bill Kunstler. Reber, like so many members of the National Lawyers Guild, struggled in the legal trenches to give activists some extra room to fight for change. He was a member of the Military Law Task Force before the MLTF was formed, spending a year in Iwakuni, Japan, as part of the Guild’s Military Law Office during the Vietnam War, defending Marines who resisted. The Marine Corps Air Station at Iwakuni was where several Marines got in trouble for passing out copies of the Declaration of Independence on the Fourth of July, while the Commandant was saying in a speech that “the Declaration of Independence is just as alive today as it was in 1776.” In Iwakuni, however, authorities declared the document being distributed as a “Communist Declaration of Independence” because it called for “the overthrow of the government.” Many years later, when I mentioned it, Reber waved it off as no big deal, saying no charges were ever lodged. But Reber’s presence, and that of the Military Law Office, helped give those Marines the wherewithal to commemorate the Fourth by suggesting that “it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish (the government), and to institute new” government if the old one is not securing their unalienable rights.

He later spent time with the Wounded Knee Legal Defense/Offense Committee and was part of the legal team that defended members of the American Indian Movement and its supporters in the case of State v. Nuwi Nini. Typically, for Reber, this was not a high profile case. It didn’t involve AIM leaders like Russell Means. But the result was remarkable. The case was dismissed when the judge determined, after weeks of voir dire of prospective jurors, that it would be impossible to find a fair jury. Since then, jury selection has become a fine art in major cases and jury consultants are in demand. Then, it was a band of volunteer legal workers and lawyers who interviewed neighbors of prospective witnesses and managed to prove that pretty much everyone in the huge jury pool had made up their minds. It may still be the only case dismissed because there were not enough jurors to give the defense a fair trial. I have cited it a few times in my career without similar success.

That was what Reber was all about. When he, along with other southern white activists, was asked why he joined the movement, he didn’t indulge in much introspection or deep political analysis. When he got involved, he didn’t think about why. “It was,” he said, “just what I thought needed doing.” Years later, reflecting on it further, his answer was the same. He got there, he said with a shrug, through the Southern Student Organizing Committee and SNCC in its Black Power period and the ACLU. And, he added, “I sure am glad it happened.” Those who knew him and those for whom he worked are also glad it happened. He was a force in the courtroom. He was a people’s champion.

Rest in power, Reber.