Published by The University of North Carolina Press

Page Count: 176

Publication Year: 2017

Reviewed by Matthew Rinaldi

The U.S. military, during its war in Vietnam, witnessed such a high level of disintegration that Col. Robert Heinl was caused to write in the Armed Forces Journal in 1971:

“By every conceivable indicator, our army that now remains in Vietnam is in a state approaching collapse, with individual units avoiding or having refused combat, murdering their officers and non-commissioned officers, drug-ridden, and dispirited where not near mutinous.

Elsewhere than Vietnam, the situation is nearly as serious…Sedition, coupled with disaffection within the ranks, and externally fomented with an audacity and intensity previously inconceivable, infests the Armed services.”

This rebellion had many causes and little central leadership. The early voices of dissent came from veterans of the fighting who saw the political reality on the ground. Spec. 4 Jeff Sharlet, trained to be a translator of intercepted messages for the Army Security Agency in 1963-1964, returned to civilian life and started the newspaper Vietnam GI, an explicitly anti-war paper that circulated widely. Master Sgt. Green Beret Donald Duncan returned in 1965 to tell Ramparts magazine, “The whole thing was a lie. We weren’t preserving freedom in South Vietnam. There was no freedom to preserve.”

The horrors of the war, from the massacres of civilians and the murder of prisoners to the destruction of entire villages, rattled many U.S. soldiers, draftees and enlistees alike. Spontaneous acts of resistance increased. In 1967 Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) was formed, and at its peak had over 25,000 members.

Stateside, three soldiers at Fort Hood refused orders to Vietnam in 1966 and became known as the Fort Hood 3. In the same year Capt. Howard Levy at Fort Jackson refused to train soldiers heading to Vietnam and Pvt. Howard Petrick was threatened with court-martial for having anti-war literature in his locker. In 1967 Pvt. Andy Stapp at Fort Sill was court-martialed for refusing to open his locker, which MPs broke open with an ax, uncovering a stash of anti-war literature.

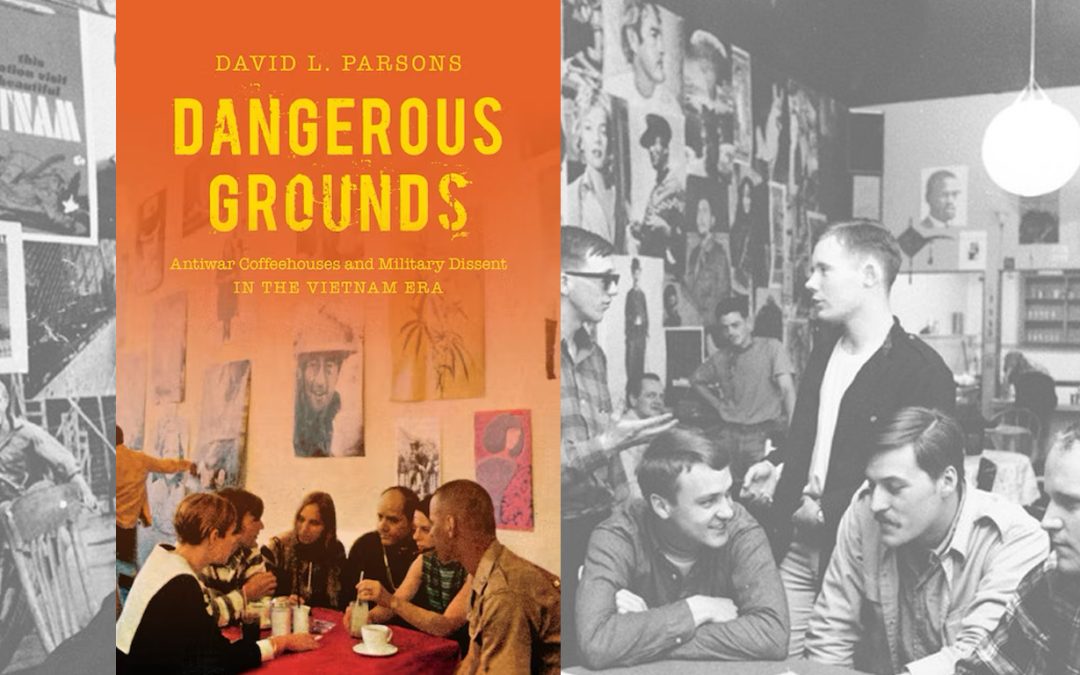

The civilian anti-war movement was not slow to respond. In early 1968 Fred Gardner and Donna Mickelson opened the UFO in South Carolina, the first anti-war coffeehouse designed to attract counter-culture GIs at Fort Jackson. Its success led to the creation of anti-war coffeehouses and counseling centers at most major U.S. military bases, which nurtured and supported the growing GI movement. It is these coffeehouses which are the focus of Douglas Parsons’ new book, Dangerous Grounds.

The coffeehouses brought together civilian organizers and active duty military personnel in a national network. It was the only ongoing organization with the ability to connect soldiers from different bases and branches of the service, providing not only a space for outreach but also an off-base location for planning events and producing anti-war newspapers. Financing was provided by the United States Servicemen’s Fund (USSF), which allowed for the mass printing and distribution of literally hundreds of anti-war papers focused on a GI audience. What we now simply call “the GI movement” was larger and more nuanced than just the network of coffeehouses, but these centers were a durable aspect of the “externally fomented” sedition referenced by Col. Heinl.

Parsons tells the story of USSF and the coffeehouses by focusing on three; the UFO in Columbia, South Carolina near Fort Jackson, the Oleo Strut in Killeen, Texas near Fort Hood and the Shelter Half in Tacoma, Washington near both Fort Lewis and McChord Air Force Base. By telling the parallel stories of the coffeehouses, the politics of the towns where they operated and the scope of the anti-war movement at each base, Dangerous Grounds effectively shows what worked well and what failed. Only the Shelter Half existed in a town with a large left-wing support movement; both the Oleo Strut and the UFO had to battle the local politicians, and the staff of the UFO were ultimately arrested and jailed. All three aided large GI resistance movements, but Fort Hood ultimately built the most successful movement.

Fort Hood was especially volatile, for reasons unique to the U.S. war in Vietnam. While much of the resistance came from draftees, who were in for two years, far more sustained rebellion came from GIs who had enlisted and were in for three years. Many enlisted because the draft seemed inevitable and young men wanted to choose a particular branch of service. Far more were facing some form of criminal charges, and were given the choice of jail or enlistment. They were hardly volunteers.

In the years of the Vietnam War, U.S. soldiers only faced one mandatory tour of duty in the combat zone. A draftee went through training, did a tour of duty, and then had only a few months until discharge. Enlistees came back from Vietnam, deeply affected by their experience, and still faced more than a year of additional time in uniform. At Fort Hood, with over 40,000 soldiers, it is estimated that in the late sixties over 15,000 were restless, disaffected Vietnam veterans.

When soldiers from Fort Hood were ordered to riot control duty in Chicago in 1968, the situation was explosive. Hundreds of soldiers, many of them Black combat veterans, gathered for a “rap session” that lasted all night; in the morning 43 were arrested and charged with disobeying orders. The response throughout the base was nearly open rebellion. The Oleo Strut went on the help organize demonstrations in Killeen and produced thousands of copies of Fatigue Press, the newspaper written and distributed by GIs.

The story of the movement and the coffeehouses which supported it is not widely known. As someone who worked at the Shelter Half and on the staff of the USSF, I can vouch for the close to pinpoint accuracy of Dangerous Grounds. Parsons should have conducted more live interviews; he only spoke to six people, only one of whom was a veteran, relying primarily in the written record. He would have learned much from vets who worked at the coffeehouses, like Hal Muskat, and from more organizers, like Judy Olasov, who worked at the UFO, set up a coffeehouse at Fort Leonard Wood, and then worked at the Shelter Half. Parsons has not written a complete account.

Dangerous Grounds also suffers from some omissions. There is little exploration of the role of left-wing parties in the coffeehouses or in the GI movement, despite the fact that the Progressive Labor Party, the Socialist Workers Party and the Spartacist League all sent cadres into the military. He misidentifies Andy Stapp as a convert to the Socialist Workers Party when in fact Stapp joined the Workers World Party. This small detail had a major impact when Stapp’s group, the American Serviceman’s Union, became significant at Fort Lewis.

Dangerous Grounds also makes no mention of the NLG, despite the fact that the Guild sent law students to most coffeehouses during the summer of 1970 and helped establish the Pacific Counseling Center, which brazenly sent organizers to the Philippines. In the epilogue, Parsons covers the G I Rights Network and mentions Coffee Strong at Fort Lewis (now Lewis/McChord) and Under the Hood at Fort Hood, but he makes no mention of the Military Law Task Force. Finally, Parson’s book is well-written, but it cannot be called a compelling read.

Despite these limitations, Dangerous Grounds is important and full of useful information. For a more complete and compelling introduction to the GI movement during the Vietnam War, I have to recommend David Zeiger’s excellent DVD, Sir! No Sir! Parson’s himself pays Zeiger’s film the ultimate compliment – he draws on it extensively.

Matthew Rinaldi worked at the anti-war coffeehouse at Fort Lewis from 1969 to 1971 and was on the staff of the USSF from 1971 to 1973. He became an attorney in 1983 and is currently on the MLTF steering committee.