[Update]: In a public statement issued on 8/22/13, Pvt. Manning disclosed that her name is now Chelsea Manning, and that she is a female. Going forward, we will honor her request to use her new name and appropriate pronouns, in support of her transition.

Today, Bradley Manning was sentenced to 35 years for the “crime” of revealing the seamy underside of US diplomacy and war-making. The sentence is substantially less than 60 years the prosecution asked for, but greater than what the defense requested. It was predicated on alleged damage done to the US, though it remains unclear what actual damage, aside from embarrassment, occurred. Indeed, the idea that transparency is damaging is one that should shock the conscience of any patriot, if one defines patriotism as something other than blind obeisance to whatever one’s government says.

Manning’s defense attorney, David Coombs, told the court that “(h)is biggest crime was he cared about the loss of life he was seeing and was struggling with it.” That, in fact, is what drove the government in its excessive and relentless attacks, inside and outside the courtroom, on Bradley Manning. That is what Barack Obama’s promise of the “most transparent” administration in history has devolved into.

Everyone in the country; nay, everyone the world over, should be outraged at his prosecution and sentence. But for Manning, Reuters still would not know what happened to its correspondents, Saeed Chmagh and Namir Noor-Eldeen, the day they were gunned down by an American air strike. And the world would not know the callousness of the Americans doing the killing, who had no regrets about also shooting a man and a young boy who came to assist the wounded and dead.

So, what is the legacy of Bradley Manning, his prosecution and sentencing? It dates back some 40 years and tells us more about the shift of power to an ever-more-secretive, imperial and imperious government from a population that has become less resistant and more pliable.

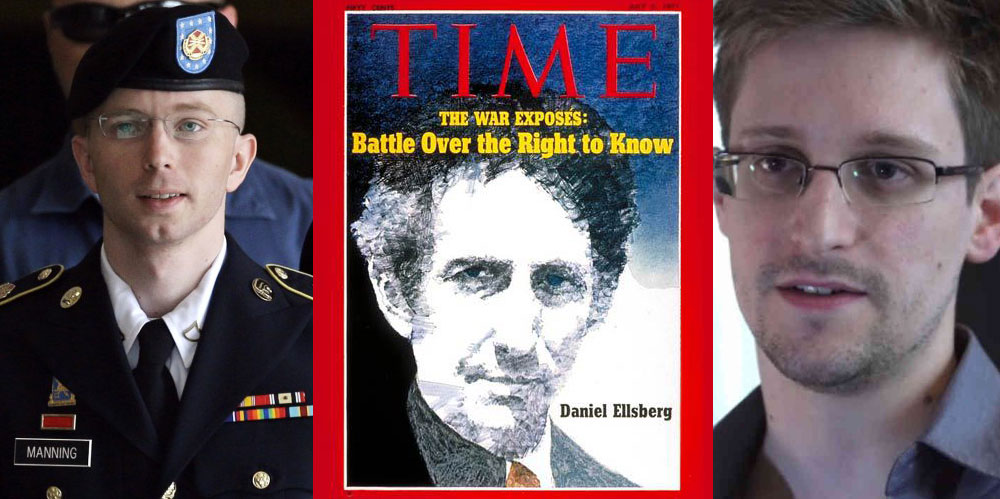

What should become an iconic photograph of Daniel Ellsberg shows him in front of his bookcase with a handwritten sign in large letters saying “I was Bradley Manning” and, under that, in smaller letters, “Pentagon Papers 1971.” There are striking parallels between Ellsberg and his collaborator, Anthony Russo, and Bradley Manning and now, Edward Snowden. All had security clearances giving them access to classified information. All became disillusioned, or at least disaffected, by the US government’s failure to level with the American people about issues critical to their lives. All became the targets of aggressive prosecutions with the president leading the charge.

There are, however, significant differences as well. The information Ellsberg and Russo leaked was more highly classified than that leaked by Manning and Snowden. The New York Times and the Washington Post responded to Ellsberg and Russo and determined to publish the Pentagon Papers in the face of law suits from the government. Only Wikileaks would take Bradley Manning’s calls. The Times and Post stood behind Ellsberg and Russo but the Times, even after publishing some of Manning’s revelations, abandoned him under cover of its dispute with Wikileaks. Most importantly, the prosecution of Ellsberg and Russo collapsed and the charges were dismissed in the light of government misconduct. While it remains to be seen what happens to Snowden, Bradley Manning was tried and convicted despite his being proclaimed guilty by his commander in chief before charges were even brought and being subjected to what the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, Juan Mendez, found to be “at a minimum cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment in violation of article 16 of the convention against torture (emphasis added).”

One must ask, what has happened in the last 40+ years that has led to such widely disparate outcomes. Is it simply a matter of the particular facts of the cases or is it something else? While there are certainly differences, and every case should be resolved on its own merits, I must suggest that the changes that have taken place in the United States in the last two generations are of overriding importance and cannot be ignored in any complete analysis of the outcome in Manning’s case.

Shortly before Ellsberg released the Pentagon Papers, and the New York Times and Washington Post published them, an FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania, was burglarized. The main fruit of the burglary, a clearly felonious act, was the discovery of FBI documents revealing its Counter-Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO). The FBI tried to discover and prosecute the burglars, but the media spent its time exposing and condemning COINTELPRO, not delving into the particulars of the investigation and identities of any suspects. While there was a brief flurry of reporting of their contents when Wikileaks released the documents it had received from Manning, that focused more on how it would affect US prestige than whether it was moral. After Manning was identified, the significance of the revelations of government depredations was abandoned in favor of exploring Manning’s psychological status. It is hard to imagine that, if COINTELPRO were exposed today, it would be so universally condemned as it was back then. Rather, one would expect media outlets to report endlessly on the damage to government, rather than invasion of the lives of citizens. The proof is in the reaction to Edward Snowden’s revelations. The outrage over what is euphemistically referred to as government “overreaching” died down in a matter of a couple of weeks, replaced by incessant reporting on Snowden’s whereabouts and the likelihood of his arrest.

Not entirely incidentally, hardly a word has been said about Director of National Intelligence, James Clapper, who unquestionably perjured himself in testimony before the Senate. He was asked, “Does the NSA collect any type of data at all on millions or hundreds of millions of Americans?” His answer: “No sir, not wittingly.” Within weeks, that claim was exposed as a lie. No prosecution has resulted, though the Justice Department chose to prosecute Roger Clemens and Barry Bonds – without much success – for lying to Congress about their use of performance enhancing drugs. If Clemens and Bonds were high-ranking government officials, their alleged perjury would presumably have been defended as patriotic and intended to “protect Americans.”

After the COINTELPRO revelations, Ellsberg and Russo were indicted. When it was revealed that the government may have lost or destroyed evidence and that President Nixon had authorized a break-in of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office, the judge presiding over the case dismissed it. The court then would not countenance such government misconduct. Manning’s treatment by his captors and his commander-in-chief’s declaration of his guilt were of a different nature than the prosecutorial wrongdoing connected in the Ellsberg case, but it is difficult to argue that torture and condemnation by the commander-in-chief are less serious. Yet, Judge Lind could not bring herself to dismiss the charges as Judge Byrne did 40 years earlier.

In the Pentagon Papers case, Justice Black held: “Only a free and unrestrained press can effectively explore deception in government. And paramount among the responsibilities of a free press is the duty to prevent any part of the government from deceiving the people and sending them off to distant lands to die of foreign fevers and foreign shot and shell.” Two things are essential to insure such a “free and unrestrained press.” First, reporters must be free to publish and able to protect their sources. Second, they must be willing and able to do so. The former is under constant attack today, and there are precious few reporters who meet the latter criterion and fewer corporate media empires that will allow them to do so.

Today, it appears, the bogey of “terrorism” trumps everything else. Due process, privacy, free expression, all are limited by the US government under the pretense of keeping our citizenry safe. By contrast, from the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s through the massive antiwar protests of the Vietnam era, Americans rose up in the millions to assert their rights and forced the government to recognize and respect them. It is long past time to revive the resistance of those years – years that expanded rights of ordinary people and limited the power of government. If we do not, as Benjamin Franklin pointed out centuries ago, we will neither have nor deserve either security or liberty.