By Kathleen Gilberd

Memo compiled from On Watch articles and updated, September 2021

- White supremacy and extremism in the armed forces (Issue 32.3, Fall 2021)

- Recognizing and challenging racism within the military (Issue 31.4, Winter 2020)

- New DoD military Equal Opportunity instruction and how to use it effectively (Issue 31.4, Winter 2020)

1. White supremacy and extremism in the armed forces

Image Source[1]

White supremacist and neo-fascist activity within the military are long-standing problems. They go back at least to the 1970’s, when the Pendleton 14 case exposed an active Ku Klux Klan chapter at that Marine base, and further investigation revealed Klan and other right-wing organizing efforts at a number of other bases around the country. Groups like the Southern Poverty Law Center exposed organizing by a variety of racist organizations both in the military and among veterans.

Ironically, the military acknowledged these problems primarily when civilian organizations and the media brought them to the public’s attention. When enough outside pressure was brought to bear, the military responded with plans to deal with such extremism, occasionally creating new policies requiring disciplinary action or discharge of those engaged in supremacist activity. The most significant was a change to DoD Directive 1325.6 (later revised as DoD Instruction 1325.06), adding a prohibition on active participation in extremist groups and providing a loose definition of extremism. Unfortunately, these policy changes were largely ignored by commands, and little was done to address the problems. Despite changes in regulations and occasional DoD statements denouncing white supremacy and neo-fascism, little changed.

In the last several years, public attention has been drawn again to racist and neo-Nazi activity by military personnel and veterans, particularly on social media, and the military has once again made a show of addressing the issues. In October, 2020, DoD submitted a report to Congress on the presence of white supremacists in the military, describing steps being considered to deal with the problem, such as improving questions on security clearance applications, accessing and learning from FBI databases of extremist tattoos and symbols, and surveilling social media for indications of extremism. The report claimed “a low number of cases in absolute terms,” though DoD admits it does not have figures on the number of extremist incidents or of individuals disciplined or discharged for extremist activity. That same month, a Military Times survey found that more than 1/3 of active-duty troops and more than half of minority service members reported experiencing or seeing examples of white supremacist activity.

In December, 2020, Acting Secretary of Defense Christopher Miller ordered a review of “current policy, laws, and regulations concerning active participation by service members in extremist or hate group activity.” He asked for recommendations on “initiatives to more effectively prohibit extremist or hate group activity” by the end of June and recommendations from DoD’s general counsel on possible changes to the UCMJ to address extremist activity in July.

Most recently military and veteran participation in the January 6, 2021, attack on the Capital brought the problem to the forefront and forced DoD to take a new round of “action.”

On February 5, Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III ordered all military commands to hold one-day stand-downs during a 60-day period to educate servicemembers about extremism and gather feedback about their experiences and concerns. His memorandum, Stand-Down to Address Extremism in the Ranks[2] stated that:

Department of Defense Instruction 1325.06, ‘Handling Dissident and Protest Activities Among Members of the Armed Forces,’ provides the core tenets to support such discussions. Leaders have the discretion to tailor discussions with their personnel as appropriate, but such discussions should include the importance of our oath of office; a description of impermissible behavior; and procedures for reporting suspected, or actual, extremist behaviors in accordance with the DoDI. You should use this opportunity to listen as well to the concerns, experiences, and possible solutions that the men and women of the workforce may proffer in these stand-down sessions.

DoD issued a set of training and talking points for the stand-downs, Leadership Stand-Down Framework[3] []. While not a policy or regulation, the material included more detail than can be found elsewhere on reporting extremist activity and command actions against those engaging in such activity. The guidelines stated that servicemembers should report extremist activity to their commands and/or to the military’s Insider Threat program; if the member reporting the activity believes it is “in a manner you suspect violates the UCMJ” or DoD or service policies on extremism, reports may also be made to military criminal investigators. The guidelines also identified a number of actions commands could take against those participating in extremist activity:

- Counseling and corrective training

- Removal from certain duties, such as restricted area badge access, flying status, or duties involving firearms

- Reclassification

- Suspension of eligibility to occupy a sensitive position

- Denial of reenlistment or involuntary separation

- Adverse evaluations and position reassignments

- Designating off-limits areas

- Ordering non-participation in specific activities, or removal of inappropriate materials

- UCMJ Article 15 and Courts-Martial

- Article 92: Violation or Failure to Obey a Lawful Order or Regulation

- Article 116: Riot or Breach of Peace

- Article 117: Provoking Speeches or Gestures

- Article 133: Conduct Unbecoming

- Article 134: General Article (Good Order and Discipline)

Although commands were required to report back on the stand-downs, DoD has not made any summary of them public. The military press, however, has interviewed some participants, with mixed responses. Some servicemembers found the stand-downs useful, but others told Military Times and other media that the sessions were sometimes presented cynically or haphazardly. Many felt that the definition of extremism was unclear, and that they did not receive sufficient guidance on the issue.

Following the stand-downs, on April 9, Secretary of Defense Austin issued a memorandum on “Immediate Actions to Counter Extremism in the Department and the Establishment of the Countering Extremism Working Group[4] ” The memo includes four immediate actions: reviewing and updating the definition of extremism in DoD 1325.06; updating the “transition checklist” for servicemembers leaving the military to include training on extremist groups’ targeting of veterans; reviewing and standardizing screening questionnaires for potential military recruits to obtain information about current or previous extremist activity; and commissioning a study of extremism within the military, “to include gaining greater fidelity on the scope of the problem.”

The memo also established a Countering Extremism Working Group, tasked with examining how military justice and administrative policy should be used to address extremism and whether existing regulations should be revised; strengthening and supporting the Insider Threat Program; examining DoD’s “pursuit of scalable and cost-effective capabilities to screen politically available information in accessions….”; and examining means to improve training of personnel on the problem of extremism using, among other things, lessons learned from the stand-downs. On this last point, the memo specifically suggested that training cover “gray areas” of extremist activity, such as reading, following or liking extremist content in social media. The Working Group was ordered to conduct its first meeting on April 14 and, within 90 days of that meeting, to report on the status of implementation of these tasks and any additional recommendations.

While some of this sounds relatively good on paper, it remains mostly paper at this point—it is unclear whether DoD will actually take firm action against white supremacy and extremism, rather than simply promoting studies, surveys and further trainings.

By way of example, clarifying the definition of extremism was one of the immediate goals set by DoD in April. As of this writing, that has not happened. DoD did hire the Rand Corporation to make further recommendations and a plan for implementation. Their report, at Reducing the Risk of Extremist Activity in the U.S. Military | RAND[5], while useful, does not include a proposed definition of extremism, which the report states was beyond its scope.

Currently, DoD faces some backlash from right-wing elements in Congress, who claim that the military is attempting to suppress all conservative thinking and failing to address leftist dissent in the ranks. It remains to be seen how DoD will respond to this, and whether real action will be taken against servicemembers engaging in white-supremacist and neo-fascist activity. The MLTF is following this issue closely and will report on further developments in future issues of On Watch.

2. Recognizing and challenging racism within the military

People of color (POC) in the military and their advocates know that racism is an extremely serious and deep-seated problem throughout the services. From disparities in promotions and career-building assignments to strong bias in the military justice system, from abusive treatment by supervisors and co-workers to overt displays of racism like racist symbols and language, racist behavior and institutional racism are alive and well in the military. The matter is made worse by the presence and active organizing of white supremacist organizations in all branches of the service.

Yet for decades, the military has held itself out as one of the country’s best equal opportunity employers, a place where race is not a factor and racism is not permitted. While people of color in the military and their advocates know otherwise, and occasional incidents of racist violence receive public attention, the services have been able to maintain a public image of equality. Until recently. In 2017, Protect Our Defenders (POD), an advocacy group working primarily around military sexual assault, produced a groundbreaking report on substantial racial disparities in the military justice system. POD found, through Freedom of Information Act requests to the services, that African-American servicemembers received non-judicial punishment and courts-martial at significantly higher rates than their white counterparts. The Air Force was determined to be the worst offender among the services.

In response, Congress demanded an investigation into racial problems in the military, which was conducted by the Government Accountability Office (GAO). GAO’s report (GAO-19-344), released in 2019, confirmed the racial disparities identified by POD, and stated that the military had failed to identify and address the causes of these problems. GAO found that African-American personnel were twice as likely to be investigated for alleged criminal activity; that African-Americans, Latinx and males were more likely than whites or women to face general or special courts-martial in all services; that race was not a significant factor in conviction in courts-martial; and that the various services didn’t track data on race and ethnicity in the same way, causing problems in identifying racial disparities. The report made 11 recommendations for the services, most emphasizing alignment of data, but two requiring substantive reform:

Recommendation: The Secretary of Defense, in collaboration with the Secretaries of the military services and the Secretary of Homeland Security, should issue guidance that establishes criteria to specify when data indicating possible racial, ethnic, or gender disparities in the military justice process should be further reviewed, and that describes the steps that should be taken to conduct such a review.(Recommendation 7)

Recommendation: The Secretary of Defense, in collaboration with the Secretaries of the military services and the Secretary of Homeland Security, should conduct an evaluation to identify the causes of any disparities in the military justice system, and take steps to address the causes of these disparities as appropriate. (Recommendation 11)

Congress then passed legislation requiring the Department of Defense to improve the ways in which it monitors and resolves racial disparities in its justice system, and to examine the root causes of the problem. GAO testified before Congress in June, 2020, (GAO-20-648T) and reported, among other things, that the services “do not collect and maintain consistent data for race and ethnicity;” “have not consistently reported data that provides visibility about racial disparities;” that DoD “has not identified when disparities should be examined further;” that racial disparities “exist in military justice investigations, disciplinary actions, and case outcomes;” and that “DoD and the services have conducted some assessments of military justice disparities, but have not studied the causes of disparities.”

Additional pressure was placed on DoD following the use of National Guard troops against anti-racist protesters this year, and the preparation to use active-duty troops in Washington, DC. Then-Secretary of Defense Esper was criticized for referring to protests as a “battle space” and for accompanying President Trump for a photo-op at a local church in Washington, DC, after the area was “cleared” of demonstrators by federal agents.

Meanwhile, Congressional hearings and media inquiries have continued to focus public attention on racial disparities in military justice, officer promotions, other career advancement matters, etc. Thus, the military’s leadership discovered racism. On June 18, 2020, Secretary Esper announced the formation of a “Defense Board on Diversity and Inclusion in the Military” to conduct a six-month study and develop “concrete, actionable recommendations to increase racial diversity and ensure equal opportunity across all ranks, and especially in the officer corps.” He also instructed military and civilian DoD leaders to present recommendations within two weeks for immediate implementation. The Defense Board is to be followed by a “Defense Advisory Committee on Diversity and Inclusion in the Armed Services,” to continue the Board’s work after its six-month study ends. Esper also said everyone in the department should “reflect upon the issues of race, bias and inequality in our ranks, and have the tough, candid discussions with your superiors, your peers and your troops that this issue demands.” In a media release describing the Defense Board’s first meeting, DoD stated that “[t]he board’s charter looks to smash systemic racism and discrimination in any form.”

On July 15, 2020, Esper issued a Memorandum, “Immediate Actions to Address Diversity, Inclusion and Equal Opportunity in the Military Service,” ordering actions which he felt required immediate implementation. These included:

- Remove photographs from consideration by promotion boards and selection processes and develop additional guidance, as applicable, that emphasizes retaining qualified diverse talent;

- Update the Department’s military equal opportunity and diversity inclusion policies;

- Obtain and analyze additional data on prejudice and bias within the force;

- Add bias awareness and bystander intervention to the violence prevention framework;

- Develop educational requirements for implementation across the military lifecycle to educate the force on unconscious bias;

- Develop a program of instruction containing techniques and procedures which enable commanders to have relevant, candid and effective discussions;

- Review hairstyle and grooming policies for racial bias;

- Review effectiveness of Military Service equal opportunity offices; and,

- Support Military Department initiatives.

The Memorandum sets deadlines for most of these tasks. Perhaps most notably, changes to at least some of the Equal Opportunity and diversity policies are to be made no later than September 1, 2020. While somewhat skeptical that DoD will meet this deadline, MLTF will report on these changes to our members as they are published and discuss them in more detail in future issues of On Watch.

In mid-June, the Judge Advocate General of the Army announced the beginning of an assessment of the racial disparities in its justice system, telling a Congressional committee that the Army is in “the very early stages of figuring out what could cause this.” On June 30, the Chief of Naval Operations announced plans to form a task force to explore ways to remove racial barriers and improve diversity, examining problems in military justice, assignments, recruitment and advancement. Subsequently named “Task Force One Navy,” the group is also expected to examine issues of sexism and “other destructive biases,” according to a Navy media release. The Air Force, announcing that ‘something had broken loose’ within it, established an anonymous survey through the Air Force Survey Office in mid-June to query airmen and space force personnel about problems of racism. In addition, the Air Force Inspector General’s office will investigate racial disparities first in the service’s disciplinary and justice system, and then in selection of enlisted, officer and civilian leadership. Both efforts are to lead to public reports. An Air Force Task Force has also begun studying problems of racism and making recommendations, ranging from increased scholarship opportunities for ROTC cadets at historically black colleges to changes in dress and appearance standards to development of a training video on racial bias.

Across the services, leadership continues to conduct surveys, discussion groups and other methods to obtain information and gauge servicemembers’ attitudes. Critics are concerned, however, that lower-ranking personnel are less often included in these efforts, and that many are hesitant to speak freely for fear of reprisals. Most recently, Secretary Esper was quoted in Military Times on August 5, 2020:

“Defense Secretary Mark Esper said Wednesday that the moment [George Floyd’s murder] was a wake-up call not only for America, but for himself, and has shaped his recent efforts around diversity and inclusion in the Defense Department. “I don’t think what everybody appreciated ‒ at least me, personally ‒ is the depth of sentiment out there among our service members of color, particularly Black Americans, about how much the killing of George Floyd ‒ and the other incidents that preceded it and succeeded it ‒ had on them and what they were experiencing in the ranks as well.” In more than half-a-dozen sensing sessions during trips to bases around the country, Esper has sat down with troops of different ranks and backgrounds for feedback on the state of diversity and inclusion in the military. “The good news, or maybe the bad news is, it’s all consistent,” he said, regardless of service or location, in story after story.”

It remains to be seen what will come of DoD’s efforts, and how honest they are. Commissions, studies, discussions, revision of Military Equal Opportunity (MEO) training, changes to MEO and other policies and regulations, and perhaps some effort to actually look for the causes of military racism may be in our future. For cynics like this writer, the possibility that these efforts, alone, will weed out racism in the armed forces seems as likely as the possibility that sexual harassment and sexual assault have been eliminated.

Within the military, many people of color are equally cynical, having seen past efforts of this sort. Others may take advantage of new policies in the hope that real change may be made, hopefully not risking the sort of retaliation faced by survivors of sexual harassment and assault. But there are important lessons to be learned from the fight against sexism in the military. Media attention can play a significant role in holding the military to its promises. Congressional intervention, for all of its weaknesses, can be helpful in forcing policy changes that the military resists. Some internal changes ‒ take, for instance, the provision of JAG counsel to survivors of sexual assault as they navigate the reporting system and deal with command inaction or retaliation ‒ may prove valuable. And, as we have all seen, the support of outside advocacy organizations, counselors and attorneys can empower those in the military who choose to fight back, ensuring that they have real assistance in doing so.

The Military Law Task Force will continue to follow this issue, and to report on it in On Watch. We would appreciate information from readers who have experience with the new policies as they go into effect. MLTF set up a subcommittee earlier this year to work around military racism and the activity of white supremacist groups in the services. Readers interested in working with the committee should contact Jeff Lake at jeff@carpenterandmayfield.com or this writer at kmg@kathleengilberd.com.

3. New DoD military Equal Opportunity instruction and how to use it effectively

As part of its effort to address military racism, the Department of Defense (DoD) published DoD Instruction 1350.02[6] on September 4, 2020. “DoD Military Equal Opportunity Program” reissues DoD Directive 1350.2, a 1995 Equal Opportunity reg last updated in 2015. While basic tenets of the Military Equal Opportunity (MEO) program remain the same, there are interesting changes and additions.

The prior Directive prevented unlawful discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin. The new Instruction expands this to include “prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, sex (including pregnancy), gender identity, or sexual orientation” (section 1.2.a.(1)). Both policies included sexual harassment as prohibited conduct, the Directive having added this in its 2015 revision. The Instruction goes beyond the traditional MEO purview to include responding to non-sexual harassment. This clarifies DoD Instruction 1020.03, the 2018 reg which prohibits harassment, hazing, bullying and reprisals; that reg suggested that the MEO program would handle such complaints, but was remarkably vague about this.

The policy section of the new Instruction (Section 1.2) also mentions the use of anonymous complaints and prohibits retaliation against complainants. While under prior MEO programs anonymous complaints were not explicitly prohibited, it is not clear that they were given any attention. And while victims of retaliation could use other complaint procedures such as Article 138, UCMJ, or claim retaliation in violation of the Military Whistleblower Protection Act, these methods were not incorporated into the MEO program.

The old Directive discussed complaint procedures in its section on responsibilities of various offices and officials, leaving the development of these procedures primarily to the Secretaries of the individual services. The new Instruction provides more specifics on complaint procedures, though much is still left to the individual services. Like prior policy, which said that the chain of command was the “primary and preferred channel” for correcting discriminatory behavior, the Instruction states that informal MEO complaints “should” be resolved at the lowest appropriate level (section 4.1), though this is not a requirement. This section requires that, when the informal process is used, an MEO representative or a non-commander member of the complainant’s command is to initiate informal resolution procedures within three days of the complaint. The section concludes with the proviso that “[i]f the complaint is not or cannot be resolved within 30 duty days of the complainant is not satisfied with the outcome, the complainant may file a formal complaint.” The old Directive was not so specific, and it mentioned a 60-day timeline for resolution of all complaints.

Formal (always written) complaints are also discussed in much more detail, in section 4.2, which outlines the steps to be taken by MEO officials, commanders and investigating officers. When a servicemember wishes to file a formal complaint, the MEO representative must advise him or her of rights in the event of reprisals, explain the complaint process and advise the complainant of support services available, monitor the progress of investigation of the complaint, refer the complaint to the commander or appropriate supervisor within three days and, of course, follow service regulations on complaints. Commanders (COs) or supervisors must, “to the extent practicable,” initiate an investigation of the complaint. The CO then forwards the complaint and a detailed description of the facts to a level of command with a legal office (which might be a general court-martial convening authority or service headquarters).

The CO or supervisor must also notify the complainant and the person(s) complained of about the initiation of the investigation, give them information about the investigative process, closely monitor the investigation, and order the investigation to be completed no later than 30 days after it is commenced, again “to the extent practicable.” Where this is not possible, the CO must make a written request for an extension, generally for no more than 30 days. If an extension is granted, the CO must make progress reports every 14 calendar days after the request and must inform the complainant and alleged offender(s) of the request and the reason for delays. Once the investigation is completed, the CO must submit a final report on the investigation and any corrective action resulting from it to the next superior officer in the chain of command. It is noteworthy that the CO, rather than the investigator or a MEO representative, determines whether or not the complaint is substantiated and what action, if any, should be taken on it. Unless extensions are granted, this must take place within 36 duty days of commencement of the investigation.

The Instruction is a bit unclear as to who will appoint the investigating officer (IO) for a complaint, though section 5.1.c suggests that COs do so; service regs usually state that the CO will appoint an investigator, though the Air Force has used MEO representatives to conduct investigations. The IO is to present a report to the CO within 30 days if practicable. If additional time is needed, the IO must follow the same steps as the CO in requesting additional time and submitting progress reports. Again, this section is more specific than the prior Directive.

Section 9.1 discusses compliance review for investigations, requiring a review by legal counsel to ensure, among other things, that the investigation meets legal requirements, adequately addresses the complaint, and includes evidence to support its administrative findings. Section 4.3 covers anonymous complaints. Where they provide sufficient information to conduct an investigation, the CO is to handle them as he or she would other complaints under EO policy.

Anonymous complaints of sexual harassment are to be handled in accord with 10 USC 1561 if they provide enough detail to conduct an investigation. With formal or anonymous complaints, section 4.5 requires that complainants (if identifiable) and offender(s) be notified of completion of the investigation and of their right to request a copy. Section 5 covers processing of complaints and requires that COs rather than or in addition to MEO officials, “[i]nform Service members of available reporting options and procedures, to their commander, supervisor, the inspector general’s office, MEO office, or staff designated by the Military Service concerned to receive complaints. An official will be specifically designated to receive allegations of prohibited discrimination involving commanders and supervisors to ensure impartial adjudication of such complaints.”

Appeals are covered under section 5.2. The Instruction states elsewhere than the only appeal procedure for an informal complaint is the filing of a formal complaint, as did the prior Directive. Section 5.2 says that the administrative findings of the informal complaint procedure are to be set aside when a formal complaint is submitted. In formal procedures, the complainant or offender may file an appeal within 30 days of receipt of notice of the findings. While the services are to establish appeal procedures, section 5.2.c requires that the procedures include a requirement that the first level of appeal should be at least two organizational levels above the appellant’s level, where practical (a higher level than that set by the Directive). It states that the appeal is not an adversarial process and thus does not include hearing rights; that the final appeal authority is to base his or her decision on the written record and any written arguments submitted as part of the appeal; and that the (final?) appeal authority may remand the case for further investigation or sustain or overrule the findings.

COs are not required to delay disciplinary or administrative action during the appeal; the Directive had mentioned only administrative action. Finally, the Instruction states that this administrative appeal process does not apply to findings in non-judicial punishment or courts-martial. The prior Directive noted that such proceedings take precedence over administrative action or appeals. Command climate assessments (CCAs) are discussed in some detail in section 7. These must include all command members and allow members to give their opinions on the command’s handling of EO, sexual harassment and sexual assault problems. Unlike the old Directive, the Instruction gives some detail on content and procedures. The Instruction also covers diversity training within commands, in section 8, which has not been revised since President Trump’s executive order and the Office of Personnel Management memo suspending diversity training.

While this article does not discuss the details, the sections on climate assessment and training can be valuable support for formal complaints or appeals as where, for instance, a command has not made improvements after a negative CCA or the lack of diversity training heightens racist behavior. It is worth noting that the training specifically includes harassment and retaliation, and the MEO complaint procedures to be used there, and that training includes policies on dissident and protest activity. The latter includes explanation of DoD and service policies “ensuring protection of members of alleged dissident and protest activities and members who intervene on behalf of victims.” (Appendix 8A) Service regulations will need to be updated to comply with the Instruction. In the interim, commands are likely to rely on the existing regs, though the Instruction is controlling.

Assisting servicemembers in making effective complaints

A few thoughts are in order about assisting servicemembers in making MEO complaints. Many members are hesitant to do so, either because they fear retaliation or because MEO complaints are seen as useless. These concerns are not unwarranted. But it is worth pointing out to them that the new Instruction offers some protection against retaliation, and that complaints made with legal assistance are somewhat more likely to succeed.

In addition, complainants can be told that MEO complaints may not be their only option. Victims of discrimination or harassment may prefer to file complaints under Article 138, UCMJ. While 138’s are not to be used when other complaint procedures are available for a particular wrong, it is often possible to couch the complaint in terms other than racial or other discrimination if the complainant wishes to do so. Requests for congressional inquiries may be effective; while some congressional offices will be satisfied with the military’s response that the member can file a MEO complaint, more sympathetic offices can be persuaded that this is less effective and less likely to result in full relief. In some cases, Inspector General complaints may also be appropriate.

When an MEO complaint is made, MEO officers generally encourage using informal complaints or even resolving the problem through discussion with the offender rather than making a complaint. It is this writer’s experience that formal complaints are more effective, and less likely to be buried. With formal complaints, MEO officers frequently propose that the complainant simply tell them what the problem is, and that the latter writes the complaint, or ask the complainant to write out the complaint on the spot. Both methods lead to weak complaints. A better approach is for the complainant and his/her attorney or counselor to write out the complaint beforehand and present it in its final form to the MEO officer. If the officer tries to reject this or add to it, the complainant can ask where in the DoD Instruction or service reg this is authorized, which will likely result in acceptance of the complaint as is.

Complainants often simply name potential witnesses in the complaint, on the assumption that the investigating officer will interview them. This is not always the case. Investigating officers will sometimes ignore some or all listed witnesses, and in some cases will fail to interview the complainant. It is not uncommon for the investigating officer to interview superiors in the command instead, and perhaps interview friends of the member against whom the complaint is made, with the result that some investigations make a record of problems or misconduct of the complainant rather than looking into the complaint. To prevent this, it is often helpful for the complainant, with the help of counsel, to obtain written statements from the witnesses to attach to the complaint; statements made under oath reduce the possibility that witnesses will be pressured by the MEO officer or command to change or retract their statements. In such cases, it may be valuable for counsel or an independent investigator to interview the witnesses about any pressure applied to change their statements.

Some creativity is in order in considering other evidence to support the complaint. Since these are not judicial procedures, rules of evidence do not apply. Second-hand statements can be submitted, and evidence that the person complained of committed other wrongs (whether or not they involved discrimination) may be used; statements showing discrimination against others are particularly useful. Offensive emails, notes or graphics made by the offender are also helpful. The investigator should consider contemporaneous writings by the complainant, whether in the form of diary entries, letters or emails to family or friends, etc.

While the Instruction and service regulations do not suggest it, complainants may want to request discovery of documents helpful to their case: any other MEO complaints made against the offender, command climate assessments if these are not available, command reports on numbers of MEO complaints and their resolution, and even disciplinary records of the offender. It may be useful to cite the Freedom of Information Act in requesting these materials. Commands are quite likely to refuse some of these requests, with little or no authority for doing so, in which case the denial could be included in any appeal.

Complainants are entitled to see the results of the investigation, though they may be denied copies of witness statements and other evidence, or even the full text of the investigative report. The Instruction is not clear on what must be provided but, particularly where the complaint is denied in whole or in part and an appeal is necessary, the whole investigation is essential. If a firm request from counsel is not successful, in obtaining this, it may be useful to request the investigation under the Freedom of Information Act, to have a congressional office make the request, or to make a request to the appeal authority, explaining that the appeal right is subverted without the full investigation.

MLTF hopes to follow the processing and outcome of MEO complaints under the new Instruction and would appreciate hearing from members who have experience with them.

Kathleen Gilberd is a legal worker in San Diego, handling discharge review and military administrative law cases. She is the executive director of the Military Law Task Force and a member of the board of directors of the GI Rights Network.

-

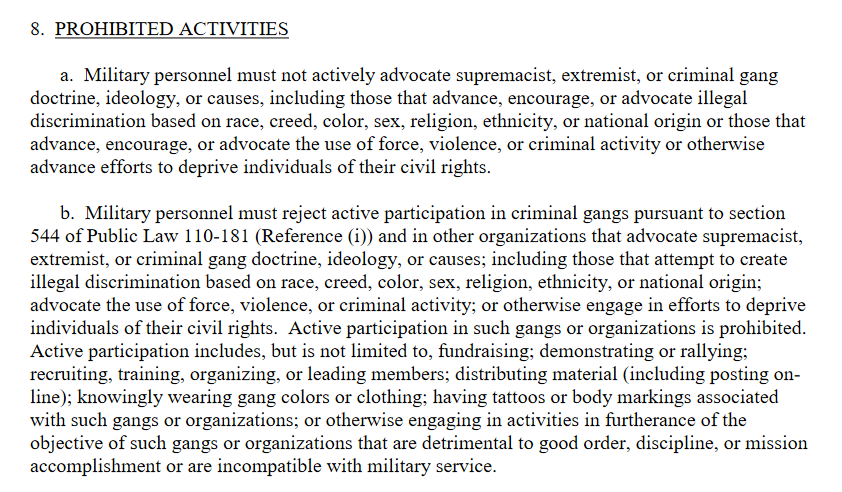

DoD 1325.06, “Handling Dissident and Protest Activities Among Members of the Armed Forces,” Enclosure 3, section 8, DoDI 1325.06, November 27, 2009, Incorporating Change 1 on February 22, 2012 (whs.mil):

[https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/132506p.pdf?ver=2019-07-01-101152-143] ↑ -

https://media.defense.gov/2021/Feb/05/2002577485/-1/-1/0/STAND-DOWN-TO-ADDRESS-EXTREMISM-IN-THE-RANKS.PDF], ↑

-

https://media.defense.gov/2021/Feb/26/2002589872/-1/-1/1/LEADERSHIP-STAND-DOWN-FRAMEWORK.PDF ↑

-

https://media.defense.gov/2021/Apr/09/2002617921/-1/-1/1/MEMORANDUM-IMMEDIATE-ACTIONS-TO-COUNTER-EXTREMISM-IN-THE-DEPARTMENT-AND-THE-ESTABLISHMENT-OF-THE-COUNTERING-EXTREMISM-WORKING-GROUP.PDF ↑

-

https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PEA1447-1.html ↑

-

https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/135002p.pdf?ver=2020-09-04- 124116-607 ↑